Educating the next generation excites and motivates many who enter the field, but many leave disillusioned and burned out these days. They deal with a variety of issues, and some of them attribute their burnout to certain factors. However, parents of the students are frequently the target of complaints.

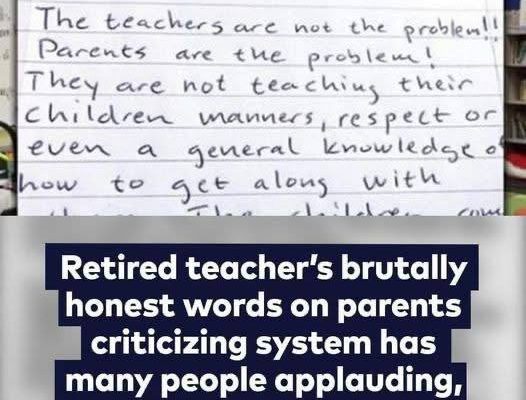

An opinion piece that a retired teacher published in a newspaper in 2017 detailing her complaints about the classroom has gone viral online ever since it was published. Many struggling teachers today seem to agree with the article’s reliability.

“Parents are the problem”

Lisa Roberson penned this letter in the Augusta Chronicle, and her words continue to spark debate about whether parents or teachers are to blame for the issues with the education system. After the pandemic, virtual classes, and students unused to a typical school setting, Roberson’s piece may carry even more weight.

“As a retired teacher, I am sick of people who know nothing about public schools or have not been in a classroom recently deciding how to fix our education system,” she begins. “The teachers are not the problem! Parents are the problem!”

She explains that parents are not preparing their kids to learn. “They are not teaching their children manners, respect, or even a general knowledge of how to get along with others. The children come to school in shoes that cost more than the teacher’s entire outfit, but have no pencil or paper. Who provides them? The teachers often provide them out of their own pockets,” she said, referring to how teachers have to use their own money to supply and decorate their classrooms. “When you look at schools that are ‘failing,’ look at the parents and students. Do parents come to parent nights? Do they talk with the teachers regularly?”

She asks if parents ensure their children come to school with the required supples and do their homework regularly. “…Do the students listen in class, or are they the sources of class disruptions? When you look at these factors, you will see that it is not schools that are failing but the parents,” she concludes. “Teachers cannot do their jobs and the parents’ job. Until parents step up and do their job, nothing is going to get better!”

The Parent-Teacher Relationship

In a perfect world, educators and parents would collaborate harmoniously. But the real world is not like that, particularly not since the pandemic. Lockdowns compelled parents to monitor their children’s education more closely.

It also gave rise to numerous debates about policies pertaining to vaccinations, gender identity, race theory, school closings, masks, and other contentious political issues that lasted for years.

All things considered, though, educators and parents share the same goal: giving kids a solid education that will propel them into the future. Instructors must impart this knowledge, which may entail coming up with inventive strategies to connect with and motivate their students. Parents must also ensure that their children have the skills necessary for optimal learning before sending them to school.

Teaching them to adhere to classroom regulations, complete their assignments, be punctual, and other things can be part of this.

However, parents may not be able to involve themselves in their children’s education for a variety of reasons. At the same time, overactive parents can cause just as much difficulty, perhaps more.

“Ghost parenting may be impacting a certain subset of students, but helicopter parenting is probably more impactful on the problems that we are seeing today,” says Scott A. Roth, PsyD, a New Jersey certified school psychologist.

“We have many children who have never been permitted to feel disappointment or frustration because parents swoop in to prevent it from happening. This can cause a child to not trust that they will ever be able to solve their own problems.”

The parent-teacher dynamic is therefore more difficult to manage than it has ever been. During the pandemic, some students fell significantly behind their peers. The widespread lack of teachers is exacerbating the fatigue and burnout experienced by those who remain in the classroom. Many claim that since the pandemic, children’s behavior has gotten worse, making pre-pandemic routines and techniques ineffective.

“So many routines were disrupted for students, teachers, and their families. Even for states that didn’t extend school closings, routines at home were disrupted, and that is very difficult for young minds to comprehend,” says Brandi David, MEd, a Florida-based K-8 educator specializing in mathematics and development editor for Hand2Mind.

“Relationships matter”

Maybe the need for schools to adapt to the times is something that both parents and educators can agree on. The modern world and its particular challenges have not yet been addressed by curriculums, schedules, and the like.

Inequity, teaching life skills, technology integration, and other areas are areas that schools need to improve, according to Patricia A. Edwards, Ph.D., a distinguished professor at Michigan State University who specializes in supporting literacy learning and development for families of color.

“In response to these criticisms, many education reform efforts are underway, focusing on curriculum modernization, personalized learning, increased use of technology, and a shift away from standardized testing,” Dr. Edwards says. “These changes aim to better align K-12 education with the changing demands of the contemporary world.”

In the meantime, parents and teachers need to work together to make the most of children’s education. “The best way to keep students accountable for their behaviors is to have a working relationship with the parents,” says David. “…Teachers should share with parents what they are doing, if it’s working, such as a calming corner, breathing techniques, and opportunities to correct their behavior.”

“Relationships matter,” Dr. Roth adds, “Students that feel safe and cared for learn better. Teachers that can connect with students relationally have far fewer behavioral problems in their classes.”